On June 30, 2014, I took an analog photography course with Tomás Cortés Rosellot. I used a Pentax K-1000 camera and an ALFRED Black & White ISO 200 film roll. I bought the camera at Foto Halcón on Vía Veneto when I was 16, with money I got from selling a GameCube. Today, it belongs to my friend Simón Tejeira.

These were the moments I captured:

This cat was lying next to a lottery vendor — you can see the table in the top left corner of the photo. It seemed to me that it was looking toward the future with a serious yet optimistic expression. Perhaps that optimism reflects what I felt — and still feel — about Panama: a place of opportunity for people from all over the world.

I couldn’t leave out a photo of Tomás, the teacher. A top-tier artist and a genuinely good person.

The Pentax K-1000 I used had a broken light meter, so I had to guess the settings manually, with some help from others who had functional ones. On the left side of the photo, you can see my friend Alfonso Grimaldo, also taking his first shots. I’ll have to ask him for the mirror image of this one—if he took it.

The entrance to Salsipuedes — a narrow alley full of colorful vendors that has earned its place in Panama City's folklore. The name means “get out if you can,” a playful reference to how crowded and winding the alley can be. I’ve heard that, in the past, you could see the ocean at the end of the alley.

Both on Avenida Central and in the Calidonia area, there are several shops that buy gold jewelry, likely to melt down and resell. This particular shop caught my eye because it stood out from the rest of the building due to its upkeep. A clear case of “the master's eye fattens the horse” — or in this case — the owner’s eye leaves no doubt about the nature of the business, thanks to the painted walls.

This is one of the corners at the intersection of Calle K and Avenida Central. To me, it's one of the best examples of the thriving commercial activity on Avenida Central. The contrast between the building's architecture and the signage shows that this is a living, breathing place — not a monument, as some might wish it to be.

My friend Ana Elena Tejera appears in this photo buying pixbae — or pejibaye, as I learned to call it in Costa Rica when I was little. Pixbae is a starchy, savory-sweet fruit from a type of palm, typically boiled and eaten as a snack in Central America. This is a typical scene from Avenida Central and, more broadly, from Panama City.

Meet Doña Luz. She works almost every day selling vegetables at a stand on Avenida Central. In this photo, she’s wearing her hair rollers, getting ready for the rest of the week. I promised her I would bring this photo framed. I still need to keep that promise.

Near Doña Luz’s stand, you can see a wide variety of food — one of humanity’s most basic needs — for sale. It’s incredible how interdependent we’ve become.

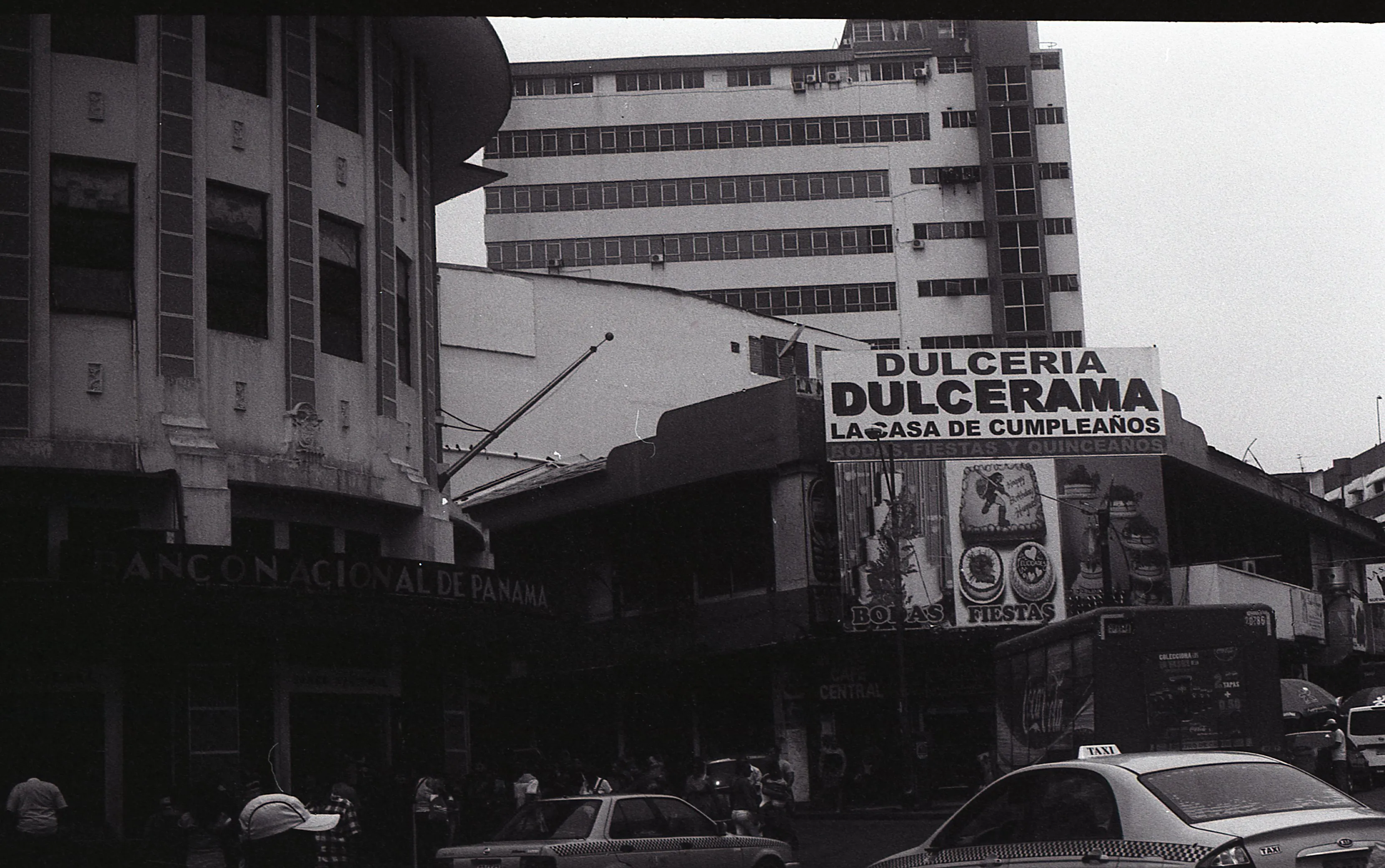

Panama City is full of businesses called “casa de” — like Casa de las Baterías (House of Batteries), Casa de la Tolda (House of Tents), and in this case, the Casa del Cumpleaños, Bodas, Fiestas y Quinceaños (House of Birthdays, Weddings, Parties, and Quinceañeras). These shops often display photos or cartoons of their products so everyone clearly understands what they sell — even though the names are already quite telling.

A photo taken outside a shop owned by members of the Emberá and Wounaan Indigenous communities, to which my friend Sara Omi belongs. In this shop, they sell fabrics designed by Emberá and Wounaan artisans, which are then reproduced and imported from Asia. Aside from perhaps the Canal, I can’t think of a better example of Panama’s commercial spirit than the outsourcing of an ancestral tradition to factories overseas.

This building features a mosaic depicting the arrival of the Spanish to the Isthmus. Another living monument with daily life flowing through it on Avenida Central.

Just like Cantonese ham pao and the Greek gyro, pizza has become an integral part of Panamanian culture. Here on Avenida Central, we find clear evidence of that.

This slightly overexposed photo, accidentally so, shows a completely abandoned neoclassical building. It appears to have no roof — only the facade remains, gradually being overtaken by plants and vines. I hope that one day an entrepreneur with enough capital rescues this monument.

These two photos are from Plaza de Santa Ana. The arrabal of Panama City — the area outside the city walls and beyond the Puerta de Tierra — was known as Santa Ana. The division between the arrabal and the formal city shaped much of Panama’s urban history. The poet Demetrio Herrera Sevillano even wrote a famous poem about this place: Parque de Santa Ana. Today, it sits at the edge of Panama City’s historic Casco Antiguo, which has been slowly restored over time.

As in every Latin American plaza, a Catholic church is never missing. Though fewer and fewer parishioners seem to attend these days, it remains an important presence in the area.

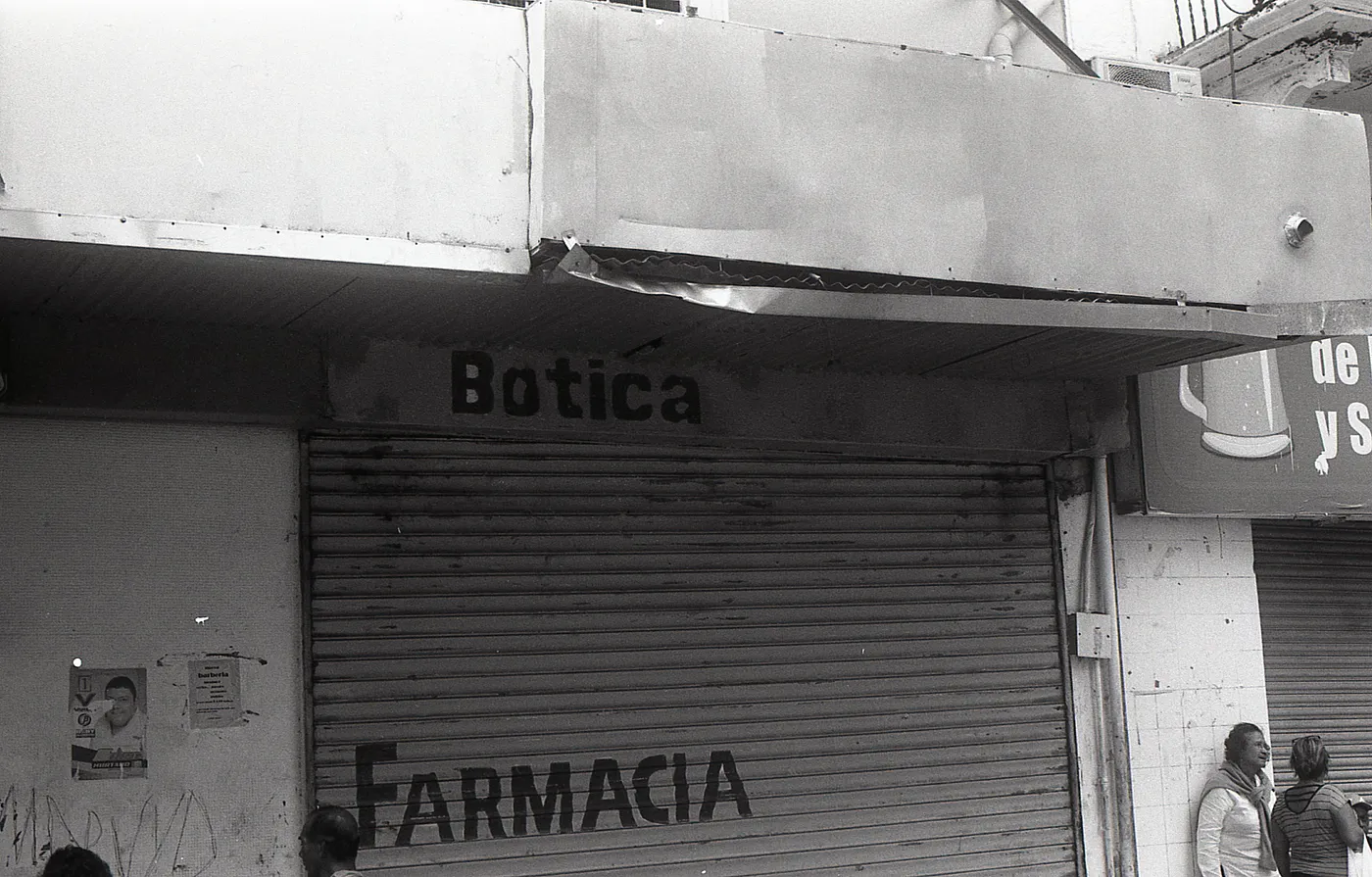

I took this photo to highlight how our language has changed over time. No one used to say farmacia — it was always botica. I always remember my grandmother, Aida Gurdián, asking me to stop by the botica to get her something.

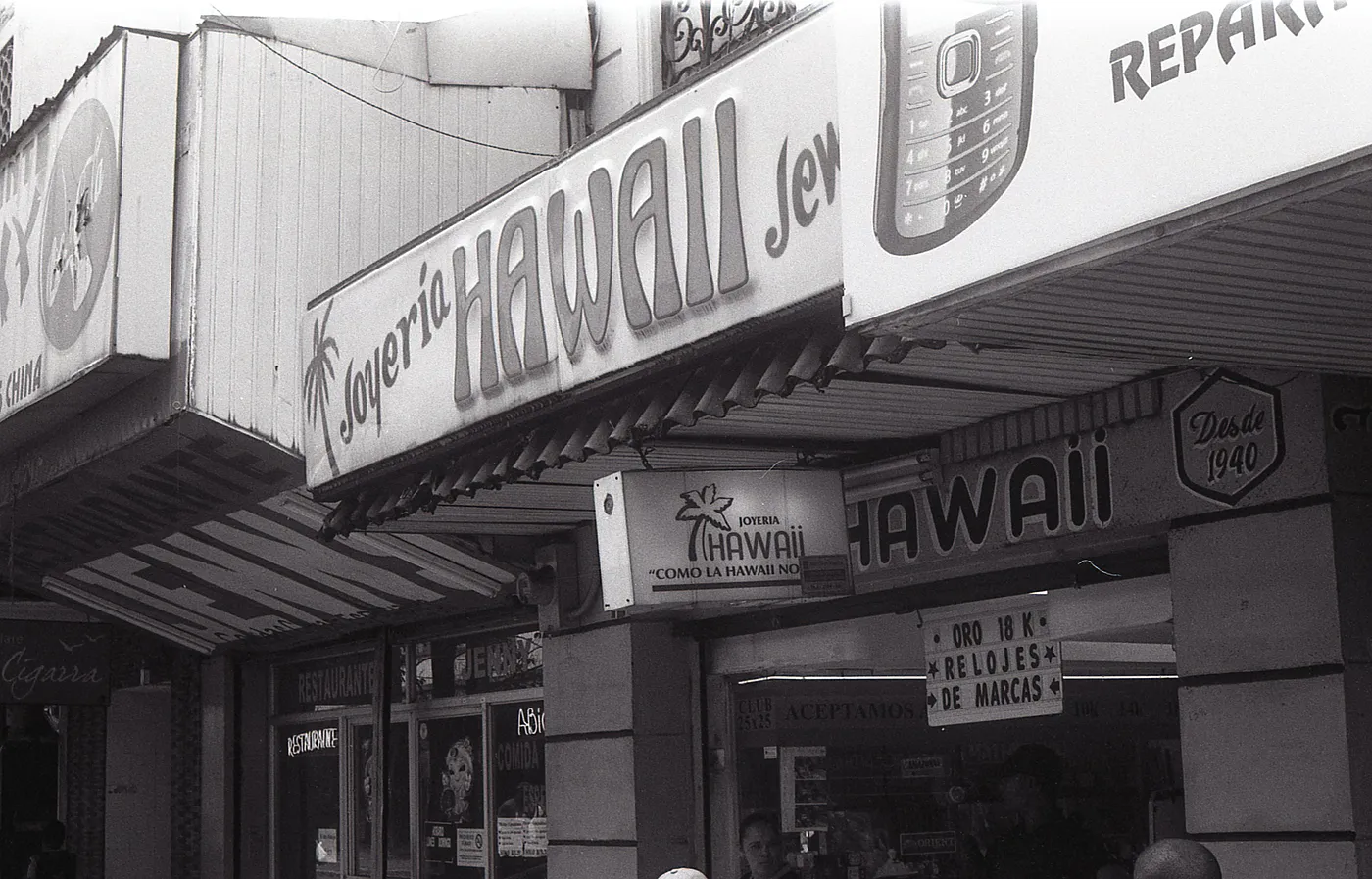

Hawaii Jewelry — “Como la Hawaii no hay” (There’s nothing like Hawaii) — once again shows the commercial face of Avenida Central. This is the part of Panama City that truly resembles many other Latin American cities, where pedestrian streets are filled with all kinds of shops.

The National Bank of Panama is not a central bank — because Panama doesn’t have one. The Constitution of 1904 — which I wish we could emulate today — included an article that set Panama’s economic history on a completely different path from its neighbors:

Art. 117. “There shall be no legal tender paper money in the Republic. Therefore, any individual may reject any bill or other note that does not inspire confidence, whether of official or private origin.”

Monetary freedom remains — even today — a foundational pillar of Panama’s economy.

This marks the end of the daguerreotype’s first journey, but there are still many moments to capture and many stories left to tell.